Strengthening Our Sensitivity When Caring for Older Adults

By Dr. Valerie Hart Quezada, Team Physician/Geriatrician, VITAS Healthcare

If we believe in stereotypes, older adults are all the same. Yet this fast-growing population is very complex and diverse. They defy a simple description because chronological age is not the same as physiologic age.

Both Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger are in their late seventies while living robust, active and independent lives. Contrast this with a frail individual of the same age living in a nursing home with balance and mobility issues who relies on support for daily living activities.

Approaching the Older Patient

Because we age in different ways, it’s important to know as much as possible about the patient we are treating and cultivate skills to match care to their health, functional status, priorities, and life expectancy. It is not enough to know age and comorbidities only.

The baby boomer population is living longer yet doing so with chronic illnesses. Often, health professionals are not well prepared to care for patients with multiple chronic conditions and have a harder time understanding disease trajectories. The “silver tsunami” of 73 million individuals in the US will require the mindfulness and holistic care of clinicians.

Physiologic vs. Chronological Age

The normal aging process produces an increase in hearing and vision issues, frailty, sleep disturbances, urinary tract infections (UTIs), potential falls, gait and balance issues, and osteoporosis.

How the body manages these changes will depend more on physiologic age than chronological age.

- Chronological age is the number of years, months, days since birth.

- Physiologic age is the patient’s functional age based on their lifestyle, diet, exercise or fitness level, and even education.

When aging, cellular and molecular damage contribute to a decrease in physiologic reserve, or the body’s ability to withstand stress and recover from illness. The loss of muscle mass, increase in cortisol, and changes in hormones and blood pressure can affect homeostasis. With decreased physiologic reserve, small “insults” can result in significant decline. A new medication can lead to acute renal failure. Contracting pneumonia can turn into respiratory failure. A minor illness or even dehydration can produce delirium.

Suppose an 85-year-old who is robust, independent, and perhaps still driving gets a UTI. They may experience a dip in functionality but can likely recover quickly. Another 85-year-old who is weaker and frail may also acquire a UTI—and may not be able to recover to baseline.

Applying the 4M’s to Determine Health Status and Goals

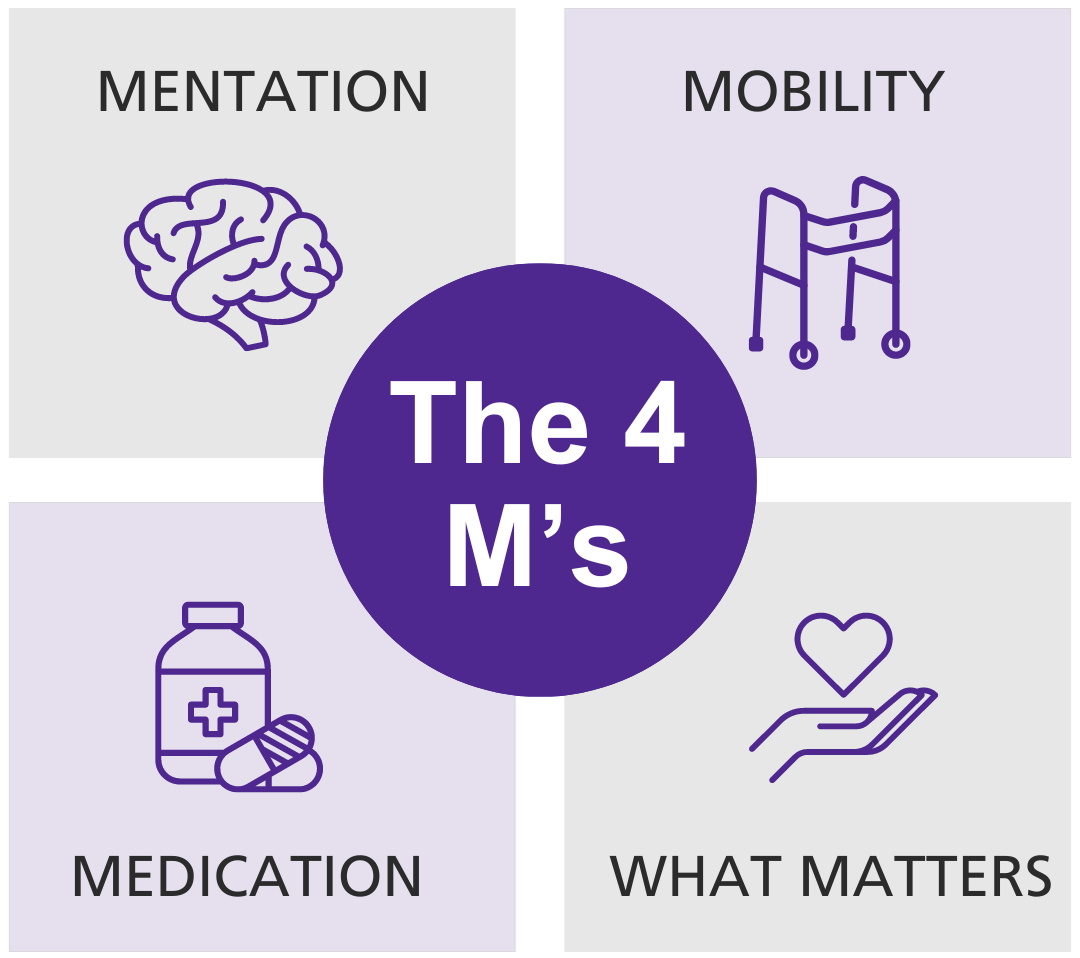

Developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the “4M’s” help healthcare professionals gauge the status of their patients. They are:

- Mentation, which is the patient’s presentation of dementia, delirium, or depression. What is their mental state? Do they have cognitive challenges or are their typical age-related responses?

- Mobility or their ability to get around. Do they use a cane or rollator? Do they need to? Older adults value being independent, so we need to identify when they start to become frailer and find ways to address barriers to being more active.

- Medications: Review these and identify what does not belong and discontinue. Ensure they understand the medications they are taking. Also, can they manage their medications?

- What matters most? Asking this question will help you identify what their values and goals are. These may vary by cultural or religious affiliation, life experiences and diseases. Do they want to be more active? Spend more time with family? What will help them achieve what matters most to them?

A fifth “M” can be multimorbidity if the patient is experiencing several chronic conditions.

Open-Ended Questions: What HCPs Can Ask

Remember that most older adults do not want to become a burden to loved ones. When they express this to us, it is a good place to start the conversation. This is an ongoing discussion because it can change for the patient over time, as their serious illness progresses. Here is a sampling of questions:

- What do you think is going on with your health? This enables physicians to prognosticate.

- What do you think the healthcare system or I can do for you? Identifies the patient’s expectations.

- Is there something you want to do in the future? Or, what activities do you find enjoyable that may have been disrupted? Physical therapy may help them increase their abilities.

- Who is important in your life? How often do you see them? This can reveal social deficits and isolation.

- Are you able to care for yourself? They may not reveal deficiencies unless asked. Minor interventions can help.

Once assessed, acting on these responses can help us align the care plan with what matters most to the older adult. If opting for hospice and palliative care, the patient receives wholistic care that includes medical, psychosocial, and spiritual support. Sharing information about the Medicare Hospice Benefit, which covers 100% of hospice services under Medicare Part A, can ease the patient’s mind about financing this type of end-of-life care.

Respect: The Key to Sensitivity

Older adults are experts on aging, and it helps to show them sincerity and empathy. Because they sometimes experience ageism from their community, the healthcare system, or even their own family, they may not receive the care they need.

Breakdowns in care may happen when healthcare professionals assume all older adults are the same or focus only on the “medical” instead of the whole person. The cognitive/emotional, familial/social, environmental, and financial domains are interconnected. Taking this whole-hearted approach will help healthcare professionals provide care that enhances their quality of life.

Do you have a patient with serious illness or multiple morbidities? Could it be time to have a goals of care conversation? For assistance with this conversation or questions about hospice-eligibility, contact VITAS.